Google I/O didn't give us the Android update we were expecting—or did it??

Andrew Cunningham

The answer is that Google did announce what amounts to a fairly substantial Android update yesterday. They simply did it without adding to the update fragmentation problems that continue to plague the platform. By focusing on these changes and not the apparently-waiting-in-the-wings update to the core software, Google is showing us one of the ways in which it's trying to fix the update problem.

Consider the full breadth of yesterday's Android-related improvements: you've got an update to the Android version of Google Maps, due this summer, that incorporates some of the features of the iOS version and the new desktop version. There's a WebGL-capable version of Chrome for Android and an entirely new gaming API. A shotgun blast of improvements are coming to the Google Play Services APIs. And that's to say nothing of the products that affect Google's services across all supported platforms: Google Play Music All Access (say that five times fast), Hangouts, and Search improvements.

In iOS, most of these changes would be worthy of a point update, if not a major version update. With few exceptions, making major changes to any of the core first-party iOS apps requires an iOS update. This method works for iOS since all supported iOS devices get their updates directly from Apple on the same day (device-specific updates like iOS 6.1.4 notwithstanding).

This is not true of Android. Here, we've seen apps like Gmail and services like those provided by Google Play gradually decouple from the rest of the OS. This makes it possible for Google to provide major front-facing updates without actually relying on its notoriously unreliable partners to incrementally up the Android version number on their devices. Many of the new things announced yesterday are coming to your Android device whether you're running a Nexus 4 or a Galaxy S 4 or a Sony Xperia ZL or an HTC Thunderbolt.

And therein lies a partial solution to the platform's fragmentation problem. The abject failure of the Android Update Alliance announced at I/O 2011 made it clear that getting Android hardware partners to fall in line with respect to device updates would be a Herculean (or, perhaps, Sisyphean) task. So Google has in essence done what newcomers like Firefox OS are proposing to do: apply more device updates at higher layers of the operating system, layers that don't need to be customized by OEMs and verified by carriers.

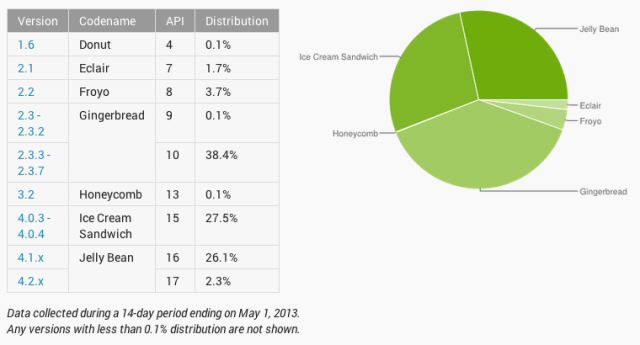

Enlarge / The state of Android updates. The picture isn't pretty.

This is probably the right way for Google to move. Baking any of these features into a hypothetical Android 4.3 would have limited their rollout to the Nexus devices for at least a few months. A small subset of devices would've waited months or even years after that. Consider that Android 4.1, which was introduced at Google I/O last year, is only installed on 26.1 percent of all Google devices a year later. Last November's Android 4.2 update is only installed on 2.3 percent of devices. Obviously, if Google wants most of its users to have access to new features, the core of Android is not the best place to introduce them.

This is not a complete solution, obviously. Lower-level, wider-reaching changes—things like Android 4.2's multi-user support on tablets, Android 4.1's Project Butter, or Android 4.0's far-reaching UI overhaul—will still require brand-new versions of Android. The same goes for many security updates and bug fixes. New Android updates won't cease to be released if the most recent round of Android 4.3 rumors are any indication.

But by tying fewer Android feature updates to the OS itself, Google gains some flexibility. The company can combat the fragmentation problem without getting into a knock-down-drag-out fight with carriers and OEMs. The ability to introduce updates through other avenues gives Google the opportunity to let its partners catch up to the latest version at their own pace without completely arresting the operating system's development. It's not a perfect solution, but it's already doing more for the platform than the Android Update Alliance ever did.

Source

0 comments:

Post a Comment